Every recorded prophecy of the world’s end in the past two millennia has failed to materialize. Over 200 apocalyptic predictions since 66 CE – from religious visions to cosmic catastrophes – have a batting average of 0%. These doomsday forecasts, spanning many cultures and eras, reveal recurring patterns of error in human belief. They serve psychological and social functions, but no faith-based end-times claim has ever been validated by reality. Modern science and historical data overwhelmingly refute the apocalyptic narrative, underscoring that such predictions are products of cultural myth and cognitive bias rather than evidence-based truth.

Background

Human history is littered with failed pronouncements of imminent apocalypse. The “Doomsday Scoreboard” – a comprehensive catalog of apocalyptic predictions from antiquity to the present – documents 201 failed end-of-world prophecies with 0 successes and 8 pending future dates. These predictions come from all corners of belief- Christian preachers, mystics, cult leaders, astrologers, self-proclaimed prophets, and even a few scientists. The dataset spans from 66 CE (when a Jewish sect expected the Messiah during Rome’s siege of Judea) to 2025 (when a TikTok-fueled Rapture hysteria fizzled) and extends into future dates set as far out as the 23rd and 24th centuries.

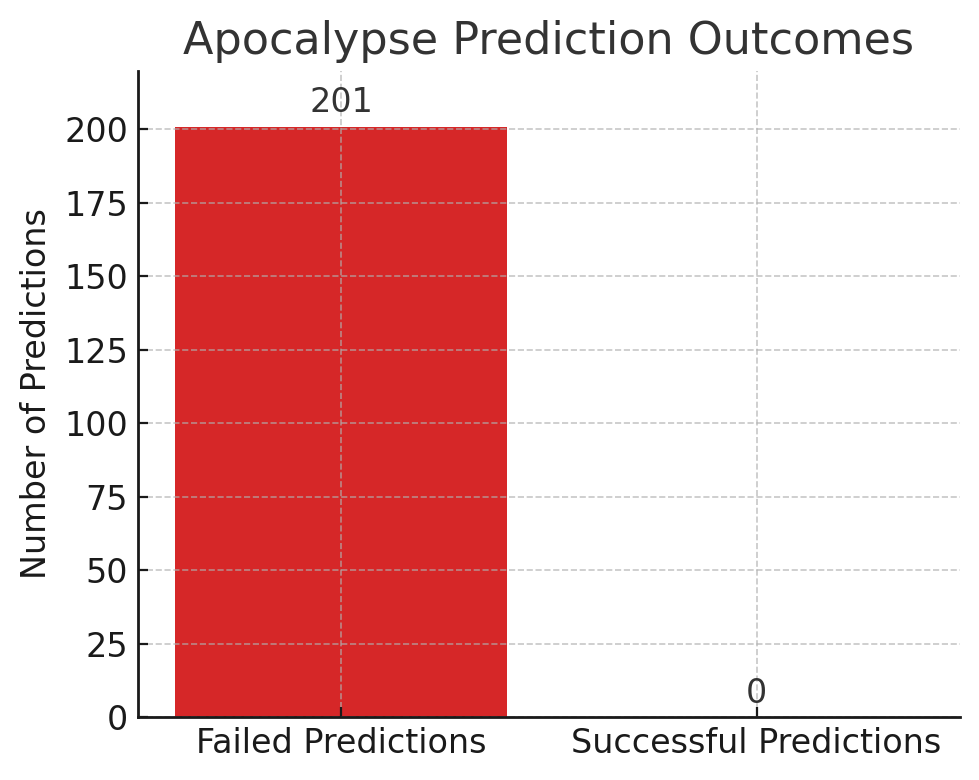

Figure 1 below visualizes the track record- 201 apocalyptic predictions vs. 0 fulfillments. Not one of these foretold doomsdays has come to pass – our planet and civilization persist. The failure rate stands at 100%, decisively debunking any claim of predictive validity for end-of-world prophecies. The perfect record of failure demands an analytic explanation. Why do such predictions arise repeatedly, and why do people believe them despite zero success? What patterns – linguistic, cognitive, cultural – underlie these prophecies? Furthermore, how does modern scientific understanding challenge and disprove each category of apocalyptic claim? The report addresses these questions with data-driven rigor and a historical perspective, aiming to reject faith-based doomsday epistemology in favor of scientific realism.

Figure 1- Outcomes of 201 Recorded Apocalypse Predictions (66 CE–2025). All have failed; none have succeeded.

Historical Timeline of Doomsday Predictions

The urge to predict the apocalypse is a deeply ingrained one. Early instances were tied to religious millennialism in the first millennium CE. For example, in 365 CE, a Christian bishop, Hilary of Poitiers, declared that the year would mark the end of the world. As 1000 CE approached, various clerics (even Pope Sylvester II) warned the new millennium might trigger Judgement Day, though historians debate how widespread the panic truly was. No apocalypse came.

From 1000 onward, failed predictions continued almost every century (see Table 1). Medieval Europe saw recurring end-time calculations, often linked to biblical numerology or celestial events. For instance, Joachim of Fiore in the 1200s calculated the Millennium to be between 1200 and 1260. Astrologers in London predicted a great flood for February 1524 under a planetary alignment, prompting thousands to flee to higher ground – but the flood never occurred. During the Reformation era, religious turmoil gave rise to more prophecies. Anabaptist visionary Melchior Hoffman insisted that 1533 would mark the Second Coming of Christ in Strasbourg. When that failed, fellow Anabaptist Jan Matthys set a new date in April 1534 and led armed followers into a doomed confrontation.

17th-century Europe (the 1600s) was rife with apocalyptic fever. Notably, Sabbatai Zevi, a Jewish mystic, twice proclaimed the Messiah’s advent – in 1648 and then recalculated for 1666. The ominous date 1666 (with “666”), combined with the Great Plague and Great Fire of London, fueled public fears of doomsday. Puritan minister Cotton Mather in New England made three separate predictions (1697, 1716, 1736) – all wrong. Enlightenment-era figures were not immune- even Christopher Columbus, in a little-known apocalyptic book, claimed the world would end by 1656–1658. All these dates came and went without an end.

The 19th century witnessed a significant surge in prophetic fervor, particularly in the United States. The Millerites, led by Baptist preacher William Miller, predicted Jesus Christ’s return in 1843, then March 21, 1844, and finally October 22, 1844 – a sequence of failures that became known as the “Great Disappointment”. Each missed date saw followers weep in despair as dawn broke on an unchanged world. Offshoots of Miller’s movement (Seventh-day Adventists, etc.) learned hard lessons about prophetic error. Around the same era, Joseph Smith of the Mormon tradition and others also speculated about end-times (Smith believed the Second Coming would likely occur by 1891, although he died well before). Folk legends even contributed- a forged prophecy attributed to the seer Mother Shipton rhymed “The world to an end shall come, in 1881,” and despite the hoax being exposed, some still fretted as 1881 approached.

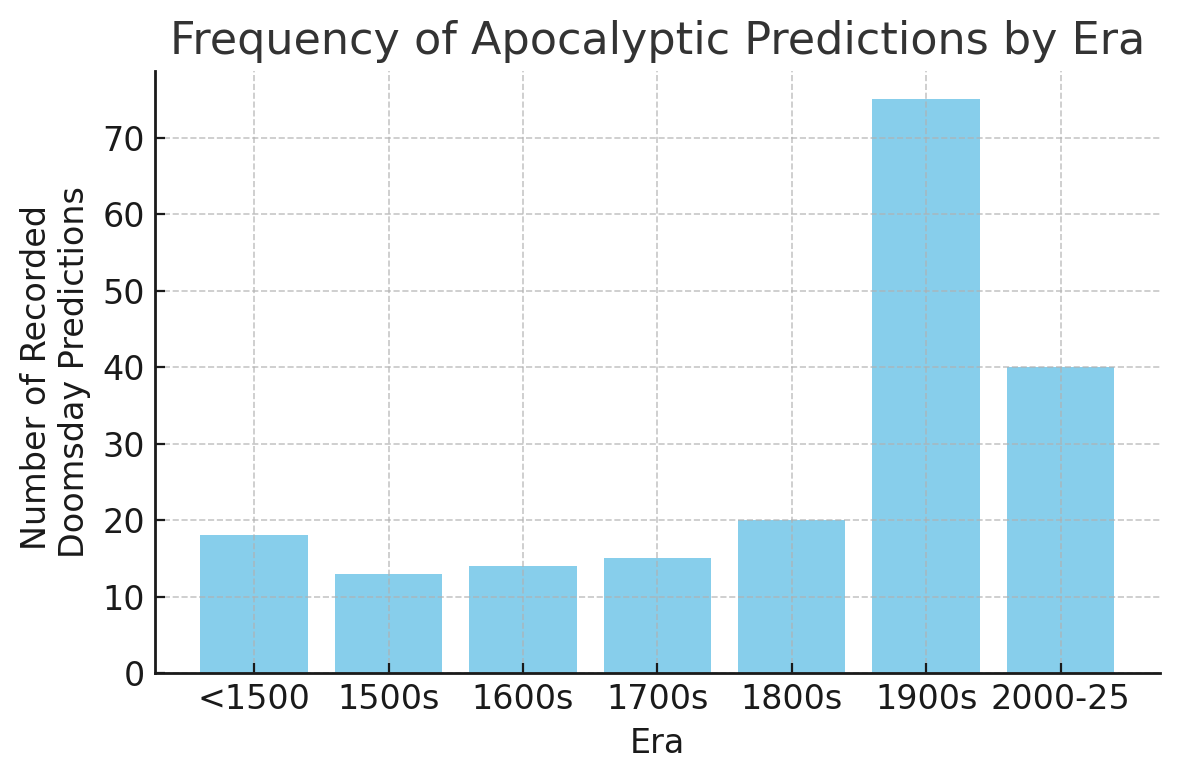

In the 20th century, apocalyptic predictions accelerated in frequency (see Figure 2). World wars, nuclear weapons, space exploration, and social upheaval all gave new fodder to doomsayers. Early in the century, the Jehovah’s Witnesses (initially known as “Bible Students”) set multiple end dates- they eyed 1914 for Armageddon (that year did bring World War I, but not the end of the world), then revised to 1918 and 1920, and later 1975, each proven wrong. In 1910, the approach of Halley’s Comet caused panic; astronomer Camille Flammarion warned the comet’s toxic tail might “snuff out all life” on Earth – people even bought “comet pills” for protection. The comet came, and Earth survived. During the Cold War, evangelical ministers like Herbert W. Armstrong and Hal Lindsey declared various dates in the 1970s–80s for the Rapture or nuclear Armageddon. All such prophecies failed despite the genuine peril of the era. The approach of the year 2000 (Y2K) triggered a frenzy – dozens of Christian and New Age figures insisted that the millennium’s turn would fulfill apocalyptic prophecy. When January 1, 2000, arrived, society did not collapse; even the much-hyped Y2K computer bug caused only minor disruptions.

Entering the 21st century, doomsday forecasts have continued unabated. A few highlights- May 2000 – The “Nuwaubian Nation” cult predicted that a planetary alignment would trigger a “star holocaust” (nothing happened). May 2003 – a prediction that rogue planet “Nibiru” would hit Earth (by Nancy Lieder) proved baseless. 2011 – Christian radio host Harold Camping gained global attention with billboards announcing Judgment Day on May 21, 2011, followed by the end of the world in October 2011. When May passed quietly, Camping revised his theology, claiming a hidden “spiritual” judgment occurred and the physical end would definitely strike in October, which also failed. 2012 – the most publicized doomsdate of recent times, sparked by misinterpretation of the Mayan calendar cycle ending on December 21, 2012. The media-fueled frenzy suggested everything from a rogue planet collision to a galactic alignment catastrophe. In reality, Mayan scholars and NASA scientists alike debunked these claims as pseudoscience and cultural misunderstanding. December 22, 2012, dawned without incident, and those who had panic-built bunkers or gathered on mountaintops slowly returned home.

Most recently, in 2020–2021, a few fringe figures linked the COVID-19 pandemic and global unrest to end-times narratives (e.g., some citing it as the fulfillment of biblical plagues, or an American pastor, F. Kenton Beshore, who predicted the Rapture by 2021 – which did not occur). In September 2025, a South African preacher’s Rapture prediction went viral on TikTok (#RaptureTok), only to flop when the date passed. Furthermore, the future is already “scheduled” with new prophecies- an asteroid apocalypse in 2026 (from an obscure sect’s teaching), and farther out, dates like 2060 (often falsely attributed to Isaac Newton), 2129 (per a Muslim theologian), 2239 (a Jewish Talmudic calculation), and 2280 (from a Quran code analysis). These remain to be tested by time, but given the perfect record of failure so far, there is little reason to expect any different outcome.

Figure 2- Frequency of recorded doomsday predictions by era. Prophecies of the apocalypse have proliferated in modern times (20th–21st centuries) compared to earlier periods, despite a consistent lack of fulfillment.

Table 1- Notable Failed Apocalyptic Predictions (66 CE – 2025)

| Date(s) | Proponent(s) | Claim/Expectation | Outcome |

| 66–70 CE | Simon bar Giora & Jewish Essenes | Jewish revolt seen as final battle before Messiah’s kingdom. | Jerusalem fell; no Messiah. |

| January 1 1000 | Various Christian clerics (e.g., Pope Sylvester II) | Millennium Apocalypse- Year 1000 feared as dawn of Last Judgment. | No evident apocalypse (panic reports disputed). |

| 1524 (Feb 1 & 20) | London Astrologers; Johannes Stöffler | Astrological Flood- Planetary alignment in Pisces to deluge London/the world. | London flood never occurred; clear skies. |

| 1666 | Sabbatai Zevi (Jewish mystic); Various Christians | Messiah & End Times- Zevi’s recalculated advent. Many Christians feared 1666 = 666 + millennium = end. | Plague and fire struck London, but world continued. Zevi’s movement collapsed. |

| 1843–1844 | William Miller & Millerites | Second Coming (Great Disappointment)- Multiple dates from Miller’s Bible calculations. | Followers left in despair when Christ did not return. |

| 1910 | Camille Flammarion (astronomer) | Halley’s Comet Gas- Comet’s tail will poison Earth’s atmosphere. | Comet passed harmlessly; no mass poisoning. |

| 1914 | Charles T. Russell (Jehovah’s Witnesses) | Armageddon- “Battle of God Almighty” to end by Oct 1914. | World War I began, but no divine apocalypse; JW’s revised timeline. |

| 1954 (December 21) | Dorothy Martin (UFO cult “Seekers”) | Alien Rescue- World to flood; aliens will save the faithful. | No flood, no aliens. Cult faced ridicule; case studied in When Prophecy Fails. |

| 1975 | Jehovah’s Witnesses (Watch Tower Society) | 6,000 Years Completed- Armageddon by fall 1975 (implied by JW publications). | Nothing happened; many disillusioned members left the group. |

| 2011 (May 21) | Harold Camping (Christian radio) | Rapture & Quake- God will take believers up and shake the Earth mightily. | Ordinary day; Camping’s followers were left bewildered. |

| 2012 (December 21) | New Age and Internet theorists | Mayan Calendar “end”- Global catastrophe via asteroid, planet X, solar flare, etc. | No apocalypse – NASA and scholars had debunked it as a hoax. |

| 2025 (September 23) | Joshua Mhlakela & TikTok #RaptureTok | Online Rapture prediction- Viral social media prophecy of immediate Rapture. | Date passed; users posted “we’re still here” memes. |

Table 1- A selection of apocalyptic predictions across history and their outcomes. None have come true. (Sources- Doomsday Scoreboard, Wikipedia.)

The historical pattern is unequivocal- prediction after prediction has failed, often dramatically or tragically. Followers have sold all their possessions, quit jobs, gathered on hilltops, and even committed suicide or murder (as in the Ugandan cult massacre after a failed 2000 prophecy) – all for naught. Each disappointment becomes part of the historical record, contributing to an ever-growing list of experiences. As of 2025, 201 apocalypses have been predicted, and not even one has occurred. The world has stubbornly refused to end on schedule.

The Rapture, the Guf, and the “Seven Signs” in Apocalyptic Predictions

The Doomsday Scoreboard, a compilation of failed apocalypse predictions, explicitly references the Rapture in recent prophetic claims. For example, it records how South African preacher Joshua Mhlakela and various TikTok users (under the hashtag “#RaptureTok”) predicted the Rapture would occur on September 23–24, 2025. This prediction stirred significant online buzz, with “Left Behind”–themed preparation tips trending on social media. In the scoreboard’s summary of statistics, “Christian Rapture” is listed as a category of apocalyptic prediction, underscoring that this concept features prominently among modern doomsday forecasts. Notably, the scoreboard highlights Harold Camping – an American Christian radio host infamous for multiple failed Rapture dates – as the individual with the most wrong predictions (six failed prophecies). Camping’s most widely publicized prophecy was that the Rapture and Judgment Day would fall on May 21, 2011, followed by the end of the world on October 21, 2011. When May 21, 2011 passed without incident, Camping revised his interpretation (claiming a spiritual judgment had occurred) and maintained that the physical Rapture would happen that October – which also failed to materialize. These instances illustrate how firmly the Rapture concept figures into contemporary apocalypse expectations documented by the Scoreboard.

In contrast, the Jewish mystical concept of the Guf – the “treasury of souls” said to hold all unborn souls – is not explicitly named in the Doomsday Scoreboard. The scoreboard does, however, include a related Jewish eschatological belief- it notes an opinion in Orthodox Judaism that the Messiah must arrive by the year 6000 of the Hebrew calendar (corresponding to 2239 CE), after which a 1000-year era of desolation would follow. This teaching (rooted in the Talmud and later Jewish tradition) reflects a timeline for the end of days, though it emphasizes a millennial deadline rather than the Guf. The Guf concept itself – which holds that the Messiah will not come until every soul in the heavenly repository has been born – is only implicit in such Jewish predictions. The Talmud (Babylonian Talmud, Yevamot 62a) indeed states that “the Son of David [the Messiah] will not come before all the souls in the Guf have been disposed of,” meaning all souls must incarnate before the end. While the Scoreboard’s entry for year 2239 CE is framed around the 6000-year deadline, it resonates with the same idea of a divinely set limit to history – a concept compatible with the Guf legend, albeit the Scoreboard does not mention the Guf by name.

As for the “Seven Signs,” the Scoreboard document does not explicitly reference a set of seven specific signs of the apocalypse. The compendium is organized mainly by predicted dates and events (e.g.,second comings, raptures, cosmic disasters) rather than by omen-like signs. However, the notion of prophetic signs heralding the end times underlies many of the listed predictions. For instance, the Scoreboard’s notes on Christian predictions frequently allude to biblical prophecies (such as the “1260 years” calculation by Isaac Newton or the “Feast of Trumpets in 2028” for Kent Hovind) – these are derived from scriptural signs or timeframes. In a more cultural vein, the Scoreboard’s mention of “#RaptureTok” trending with “left behind” tips hints at the popular fascination with signs of the Rapture (users on social media discussing how current events might fulfill biblical portents). In summary, while the Scoreboard lists concrete apocalypse dates rather than a checklist of signs, it implicitly incorporates the Seven Signs concept through the sources that inspired those predictions. Many entries are rooted in interpreting certain signs (biblical or otherwise) as indicators that the end is imminent.

The Rapture in Christian Eschatology and Predictions

The Rapture is a belief, particularly prominent in evangelical Christianity, that in the end times true believers will be suddenly taken up from Earth to meet Christ, prior to a period of tribulation on Earth. This idea is based on New Testament passages such as “we who are alive… will be caught up together with them in the clouds to meet the Lord in the air” (1 Thessalonians 4-17, NIV). The term “rapture” itself comes from the Latin rapiemur (“caught up”) used in the Latin Vulgate translation of this verse. According to this doctrine, at the appointed time God will snatch away the faithful – the dead resurrected and the living transformed – leaving the rest of humanity behind. This dramatic event is envisioned as the inauguration of the end-times drama in certain Christian theologies (specifically dispensational premillennialism). Notably, this theological interpretation is relatively recent in Christian history. Most major Christian denominations historically did not teach a two-stage return of Christ; the Rapture doctrine in its popular form originated in the 1830s, largely through the teachings of John Nelson Darby and others in the Plymouth Brethren movement. By the 20th century, the Rapture had become a core element of American fundamentalist and evangelical end-time expectations.

In practice, the Rapture concept has inspired numerous apocalyptic predictions and timetables. Many evangelical figures and groups, reading “the signs of the times,” have tried to calculate when the Rapture will occur – often with failed results. A famous early instance was the Millerite movement in the 1840s (though Millerites spoke of Christ’s Second Coming rather than a pre-tribulation rapture, the expectation was functionally similar – the faithful would be taken into salvation). William Miller, a Baptist preacher, used biblical prophecies in Daniel to predict Jesus Christ would return by 1843, and later adjusted the date to October 22, 1844. When that day passed without Jesus’ advent, the collective anguish became known as the Great Disappointment. Many Millerites had given away their possessions and awaited rapture-like deliverance; their devastation at the failed prophecy was immense, even leading to public ridicule and violence against them in some cases. The movement fractured, but interestingly it did not vanish – some followers reinterpreted the prophecy (concluding that an invisible heavenly event had occurred rather than the literal return of Christ) and went on to found the Seventh-day Adventist Church. This pattern of reinterpretation after failure has recurred often in Christian apocalyptic groups.

Throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, the Rapture continued to be a focal point of prophetic speculation. A surge of Rapture anticipation occurred in the late 20th century due to the influence of writers like Hal Lindsey. Lindsey’s 1970 bestseller The Late Great Planet Earth interpreted current events (wars, earthquakes, the restoration of Israel, etc.) as fulfillments of biblical end-time signs and suggested the Rapture and subsequent end could occur in the 1980s – approximately one generation (40 years) after Israel’s founding in 1948. In that book, Lindsey pointed to things like the increase of global conflicts, famines, and earthquakes as evidence that “the end of the world” was approaching, aligning these trends with Jesus’ prophetic words in Matthew 24 about wars and natural disasters preceding the end. Although Lindsey avoided setting a hard date, his implication of the 1980s time frame proved incorrect; nonetheless, his style of prophecy interpretation popularized the notion that contemporary events are prophetic signs. Many evangelical preachers followed suit, regularly linking news headlines to Bible prophecies to suggest the Rapture was near.

Some went further and named specific dates. The 1980s saw various pamphlets and books predicting the Rapture in a given year – for example, one well-known pamphlet was 88 Reasons Why the Rapture Will Be in 1988, which pinpointed September 1988 for the event. (When 1988 passed, its author Edgar Whisenant revised his calculations and proposed 1989, then 1993, and so on, eventually losing credibility.) The most infamous modern attempt was by Harold Camping, who predicted the Rapture would occur on May 21, 2011. Camping, then 89 years old, used numerological calculations from scripture to fix that date and spent millions on advertising this prophecy. He asserted “beyond the shadow of a doubt” that on May 21 the Rapture would strike at 6 p.m. in each time zone, sweeping true believers into Heaven and unleashing a global judgment. When the day came and went, Camping first claimed a spiritual judgment had occurred and postponed the physical Rapture to October 21, 2011, coinciding with the final end of the world. That date too passed uneventfully; Camping eventually admitted his calculations were wrong and even termed his own prognostication efforts “sinful,” noting that biblical texts like “of that day and hour knoweth no man” (Matthew 24-36) clearly warn against date-setting.

Despite these repeated failures, Rapture predictions have shown a tenacious cultural influence. The buildup to predicted Rapture dates often spurs intense activities among believers – from evangelistic crusades to life-altering personal decisions. For instance, leading up to 2011, some of Camping’s followers quit jobs or spent their life savings to warn others of the impending judgment. Each failed prophecy also generates media attention and sometimes disillusionment, yet the broader belief in a coming Rapture remains robust in many churches. Sociologists note that apocalyptic movements often use failed predictions to refine or reinforce their beliefs rather than abandon them. In some cases, the failure is rationalized as a test of faith or a miscalculation in timing (rather than a falsification of the underlying theology). This phenomenon was famously analyzed by Leon Festinger in his study When Prophecy Fails, which observed that true believers often redouble their commitment after a prophecy’s failure, seeking new explanations rather than conceding defeat. We see this dynamic in groups like the Millerites and Camping’s followers, as well as others (e.g.,Jehovah’s Witnesses, who predicted Christ’s return in 1914 and later reinterpreted it as an “invisible” spiritual arrival when the visible event did not occur).

Furthermore, the Rapture belief has significantly shaped myth-making and popular culture. It provides a dramatic narrative framework – captured vividly in fiction like the Left Behind novel series and film adaptations – of a world where in the blink of an eye, the faithful vanish and apocalyptic chaos ensues. These stories, while fictional, reflect genuine theological expectations and in turn influence how believers imagine the end times. The Rapture mythos has even informed real-world policy and politics; as historian Crawford Gribben observed, Lindsey’s prophecy themes in Late Great Planet Earth “exercised enormous influence” on American evangelicalism’s political outlook in the late 20th century, even finding an ear in President Reagan’s administration. For some, believing that the end of the world is imminent (and that one’s own generation might be the last) can motivate both religious activism (to “save souls” before the Rapture) and particular geopolitical stances (such as strong support for Israel, seen as a fulfillment of prophecy). In summary, the Rapture serves as a powerful apocalyptic idea that has fueled countless predictions, mobilized believers through both hope and fear, and become a fixture in the eschatological narrative framework of modern Christian evangelical thought.

The Guf in Jewish Mysticism and Messianic Expectations

In Jewish mystical and apocalyptic thought, a concept analogous to the Christian end-time count-down is the Guf (also called the Otzar, or treasury of souls). The Guf (Hebrew for “body”) is said to be the heavenly storehouse or reservoir that contains all souls destined to be born on earth. According to this lore, history is finite because the supply of souls is finite- when the last soul has descended from the Guf into a newborn baby, the end of days will commence. The idea appears in the Talmud – for example, Yevamot 62a teaches that “the son of David [the Messiah] will not come until all the souls in the Guf have been exhausted”. In other words, the Messiah’s arrival is contingent on the Guf being emptied of souls. This teaching suggests a divine schedule for redemption that is tied not to a specific date, but to a metaphysical quota of souls reaching fulfillment. The scriptural basis sometimes cited for the Guf concept is a verse in Isaiah, “for the spirit that envelops itself is from Me” (Isaiah 57-16), interpreted by rabbis to imply a preexistent cache of spirits.

While the Guf is a well-established theme in Jewish mysticism, it generally did not spawn the kind of date-specific predictions seen in Christian apocalypticism. Instead, it introduced a conditional element to Jewish eschatology- the community’s mandate to “be fruitful and multiply” was mystically tied to hastening the Messiah’s advent, since each birth potentially brings the world closer to emptying the Guf. In this way, the Guf belief has served to mobilize behavior (encouraging procreation and hope in redemption) rather than to calculate end dates. For example, some rabbinic legends suggest that because of this teaching, each new child born brings the world one step nearer to the Messianic age. It imbues the ordinary act of having children with cosmic significance – a form of quiet myth-making that links daily life to the ultimate redemption. This contrasts with Christian Rapture predictions that often lead followers to disengage from worldly pursuits; in Jewish communities, the Guf motif subtly encourages continuity of life and family as a pathway to God’s plan.

Historically, certain Jewish messianic movements have been aware of and influenced by the Guf idea, even if they did not reference it explicitly. For instance, in the messianic ferment of 16th–17th century Kabbalistic circles (such as those surrounding the false messiah Sabbatai Zevi in 1666), there was intense speculation about whether the cosmic conditions were ripe for the Messiah. Kabbalistic texts like the Sefer HaBahir expanded on the Guf concept, describing the store of souls in conjunction with the mystical figure of Adam Kadmon (Primordial Adam). In Sefer HaBahir, it is stated- “The son of David will not come until all the souls in the Guf are completed”, linking the idea of the souls in the “Body” (Guf) to the cosmic body of Adam Kadmon. This indicates a mythological framework in which human souls are fragments of a primordial being, and history’s culmination requires all fragments to be manifest in the world. Such esoteric teachings typically remained the province of learned mystics rather than the general populace. Nonetheless, they contributed to an overall worldview in Judaism that the timing of the Messiah’s coming, while not known exactly, has set cosmic parameters – one of which is the completion of all destined souls.

It is worth noting that mainstream Judaism generally discourages explicit date-setting for the Messiah or end of the world. After several traumatic episodes of mass messianic expectations (and disappointments) – for example, the Bar Kokhba revolt in the 2nd century or the aforementioned Sabbatai Zevi movement – rabbinic wisdom emphasized that calculating the exact time of the end was futile or even spiritually dangerous. The Talmud itself records a warning- “Blasted be the bones of those who calculate the end” (Sanhedrin 97b), cautioning against trying to predict when the Messiah will come. Therefore, the Guf concept was seldom used to mark a calendar date like “when the count of souls hits zero, on this day, Messiah arrives.” Instead, it functioned more as a narrative device expressing faith that God has a predetermined limit to how much longer the world will endure its imperfect state. It places the end of days on the horizon of inevitability without specifying its exact schedule – once the last soul is born, redemption must dawn. In Jewish preaching and literature, this often served to instill hope- just as an hourglass trickles down, so too our sorrows will not last forever because the “warehouse” of souls will eventually empty.

An interesting cross-cultural footnote is how the Guf concept entered modern popular imagination. A 1988 Hollywood film titled The Seventh Sign actually centered its apocalyptic plot on the idea of the Guf. In the movie, starring Demi Moore, the world is experiencing the biblical signs of the end (the “seven signs” of catastrophic events), and the final trigger of the apocalypse will be the birth of the last soul from the Guf. The film’s premise was directly inspired by Jewish legend – explicitly mentioning the treasury of souls – thereby bringing this mystical concept to the awareness of general audiences. In the story, when the Guf is nearly empty, catastrophic “signs” unfold and only the sacrifice of the protagonist can prevent the final emptying and thus delay doomsday. Though fictional, The Seventh Sign illustrates the powerful symbolic role the Guf plays- it is literally portrayed as the ticking clock of the apocalypse. This is a prime example of myth-making, where an ancient religious idea is adapted into a contemporary narrative of global destruction and salvation. It shows that the Guf, while not commonly invoked in real-world doomsday predictions (since Jews rarely predict a date for when the last soul will be born), nonetheless holds a firm place in the tapestry of apocalyptic thought – emphasizing the completion of a cosmic process as a condition for the end of the current world order.

In sum, the Guf concept contributes a unique perspective to eschatology- it frames the end of days not in terms of human calendars or visible signs, but in terms of a hidden spiritual metric – the quota of souls. This has shaped Jewish eschatological narrative by reinforcing the belief that there is a divinely ordained completion point to history. It imbues each birth with eschatological significance and offers a hopeful assurance that eventually, when the time (or souls) are fulfilled, the long-awaited Messiah will arrive. Unlike the Rapture, which often incites urgent apocalyptic fervor and active prediction, the Guf encourages patience and continuity – an eventual ending that creeps closer with every generation born.

The “Seven Signs” in Biblical Eschatology and Prophetic Tradition

The term “Seven Signs” is associated with the idea that a series of specific omens or events will foreshadow the end of the world. This concept has roots deep in Christian tradition and has taken various forms over time. In the early centuries of Christianity, apocryphal texts tried to flesh out the mysterious signs of the end mentioned in the Bible. One notable example is the Apocalypse of Thomas (an apocryphal writing, c. 2nd–4th century), which enumerated a set of signs heralding the final judgment. The earliest version of this text described seven signs announcing the end of the world, occurring in the last seven days of history. For instance, it predicted phenomena like waters rising, terrible heat, global earthquakes, and the resurrection of the dead as sequential signs. In later medieval tradition, this schema was expanded – the widely circulated legend of the Fifteen Signs before Doomsday grew out of the Apocalypse of Thomas, appending more signs to the list (ultimately fifteen signs over the last fifteen days of the world). Throughout the Middle Ages, the motif of the signs before Doomsday became popular in sermons, literature, and art. It appeared in works like the Golden Legend and was a familiar theme to common folk. These pre-apocalyptic portents served a didactic purpose- they were often invoked by preachers to stir penitence and alert people to the eventual certainty of Judgment Day. The specific signs varied by source, but typically included extreme cosmic disturbances (e.g.,seas rising and receding, heavenly bodies darkened or falling, great fires, general resurrection). The underlying message was clear – God, in His mercy, would signal the world’s imminent end through unmistakable events, giving the living a final chance to repent.

Biblically, the idea of signs preceding the end comes up in the New Testament as well. Jesus’ Olivet Discourse (Matthew 24, Mark 13, Luke 21) lists a number of calamities and moral conditions as “the beginning of birth pangs” – wars, famines, earthquakes, plagues, false prophets, and so on – which must occur before the end (Matthew 24-6–8). The Book of Revelation describes a sequence of prophetic events (the seven seals, seven trumpets, and seven bowls) that unleash disasters on the world. Although not explicitly named “seven signs” in Revelation, these seven judgments mark a progression toward the final outcome. In fact, some commentators refer to the section of Revelation 12–14 (which opens with the vision of a “woman clothed with the sun” and a dragon) as the “seven signs” section, since it presents seven symbolic visions of the end-times conflict. Thus, the number seven (a symbol of completeness in biblical literature) frequently structures end-time prophecies, whether it’s seven seals or seven key events. This numeric motif likely reinforced the later use of “Seven Signs” as a shorthand for a complete set of end-of-world omens.

In the modern era, especially among evangelical Christians, the phrase “Seven Signs of the End Times” (or similar titles) often appears in popular literature and media. Pastors and authors sometimes enumerate a list of seven major indicators that Christ’s return is near. These lists are not uniform, but they commonly mix biblical prophecy with observation of current events. For example, an evangelical preacher might cite- (1) the return of the Jews to Israel, (2) increasing wars and rumors of wars, (3) earthquakes and natural disasters uptick, (4) moral decay or “days of Noah” societal conditions, (5) spread of the Gospel worldwide, (6) rise of a threatening global political power or Antichrist figure, and (7) signs in the sky (astronomical portents) – as seven signs that we are in the end times. Many of these are drawn directly from scripture (for instance, Jesus also said “this Gospel of the Kingdom shall be preached in the whole world… and then the end will come,” which is taken as a sign – Matthew 24-14). These “seven signs” compilations are essentially interpretative frameworks to convince believers that prophecy is unfolding now. Ministries and publications (such as Tomorrow’s World magazine or popular televangelists like John Hagee and David Jeremiah) have produced numerous teachings along these lines, each selecting seven prominent signs. While the specific content varies, the recurrence of the number seven itself shows the influence of biblical precedent and possibly the medieval legend on the structure of modern prophecy teaching.

The purpose of delineating signs – seven or otherwise – is to create a sense of urgency and meaning about contemporary events. It is a form of prophetic rhetoric that bridges ancient texts with current headlines. For instance, during the Cold War, preachers often pointed to the threat of nuclear war as a fulfillment of end-time prophecy (seeing in it echoes of the apocalyptic battles described in Ezekiel or Revelation). They might list the development of nuclear weapons as a “sign #1” that unprecedented global destruction looms (aligning with “fire from heaven” imagery in Revelation). Another sign frequently mentioned in the late 20th century was the re-establishment of Israel in 1948 – regarded by many fundamentalists as a miraculous fulfillment of prophecy and a key trigger of the end-times countdown. The convergence of these signs in a single period (wars, Israel, global evangelism, natural disasters, etc.) is taken as evidence that the world is entering its final stage. In the 21st century, new themes have joined the list- for example, some see advances in technology (microchips, AI) as potential tools of the Antichrist’s regime (the “mark of the beast”), or they interpret events like pandemics as foreshadowed plagues.

While these modern “signs of the end” narratives often carry an implicit expectation that the decisive moment is very near, they sometimes stop short of giving exact dates (having learned from the failure of too-specific predictions). Instead, the rhetoric focuses on watchfulness– believers are urged to recognize the signs and live in readiness for Christ’s return at any time. This creates a sustained state of apocalyptic anticipation that can mobilize religious communities. It can inspire evangelical activism (spreading the Gospel with urgency, since the time is short) as well as personal moral reform (encouraging individuals to repent and commit to faith before it’s too late). Belief mobilization here is achieved not by a fixed deadline, but by a pervasive sense that “we are already witnessing the prophesied signs; the climax could happen at any moment.”

Historically, the motif of signs also played a role in myth-making beyond Christianity. Many cultures and religions have the notion that extraordinary omens will precede a world-ending event or a great transition. In Islam, for instance, there is a rich tradition of the Signs of the Hour – a collection of minor and major signs before the Day of Judgment (such as the coming of the Mahdi, the appearance of the Dajjal (Antichrist), the return of Jesus, the sun rising from the west, etc.). While not the focus of our current analysis, it’s noteworthy that the impulse to enumerate signs is a cross-cultural phenomenon, reinforcing the human desire to know the unknowable by reading meaningful patterns in history.

Returning to the Christian context of “Seven Signs,” we see it as a recurring template in eschatological teaching that fulfills both narrative and didactic functions. Narratively, it provides a sequential drama – a feeling that we are moving through chapters of a foretold story (e.g.,first this will happen, then that, all building to the finale). Didactically, it serves to remind believers of scriptural truths and to validate faith- as each identified “sign” seems to come to pass, it bolsters confidence that the remaining ones (including the Second Coming) will soon follow. However, one must also recognize that repeatedly, through history, people have believed “all the signs have occurred” and yet the world continues. For example, by 1000 AD many in Christendom thought the proliferation of war, pestilence, and schism was proof that the end was at hand (some even identified seven specific portents around that millennium). Again around the Protestant Reformation in the 1500s, signs such as monstrous births, celestial phenomena (comets, eclipses), and the Turkish invasion of Europe were interpreted as apocalyptic heralds. Failed doomsday dates often came on the heels of such fervor when expectations crescendoed.

What the endurance of “Seven Signs” rhetoric shows is its role in sustaining an eschatological worldview even when the final event doesn’t occur as soon as hoped. By continuously updating and reinterpreting the signs, apocalyptic belief systems remain adaptable. For instance, when the year 2000 passed without incident despite widespread end-times predictions, many prophecy interpreters simply moved the goalposts, finding new signs in the 21st century (like global terrorism or economic turmoil) to replace those that had become outdated. In effect, the concept of a sequence of signs provides a resilient framework for prophecy- one can always argue we are “part-way through” the signs, keeping followers engaged and expectant.

Prophetic Rhetoric, Myth-Making, and the Mobilizing Power of Apocalyptic Beliefs

Examining the Rapture, the Guf, and the Seven Signs across traditions reveals how apocalyptic concepts function in religious narratives. Each serves as a piece of the eschatological puzzle that gives believers a sense of where they stand in the cosmic timeline and what to hope for or fear next. The Rapture offers an imminent, dramatic rescue from a doomed world – it’s a promise of salvation that can be both profoundly comforting and urgently frightening (for those who worry about being “left behind”). This dual nature makes it a potent tool for religious leaders to galvanize followers- by stressing the Rapture’s nearness, preachers have filled tents and churches with people seeking assurance they will be on the right side of that divide. As history shows, the rhetoric around Rapture predictions (or analogous Second Coming predictions) can mobilize mass movements (e.g.,Millerites), inspire global evangelism campaigns, and even influence political alignments (such as Christian Zionist support for Israel, partly driven by prophecy beliefs). When specific dates are given and then fail, the rhetoric may shift – often emphasizing that the exact date is less important than the readiness of one’s soul. In all cases, the Rapture narrative contributes to myth-making by framing current events as part of a supernatural story that is hurtling toward an inevitable climax.

The Guf, while less about rallying the troops in the here and now, contributes to myth-making by providing a mystical backstory to the drama of the Messiah. It instills the idea that each human soul matters in a cosmic count. One might say it democratizes the apocalyptic process- every birth, even of a seemingly ordinary child, carries weight in tipping the scale toward redemption. The Guf concept has not commonly been used to whip up apocalyptic fervor on a specific timetable (since Judaism largely avoids that), but it has been a quiet motivator of hope. In times of despair, Jewish sages could remind their communities that God has a fixed limit – when the Guf is empty and the souls are spent, suffering will end and the Messianic age will dawn. Thus, the Guf feeds into the larger mythos of exile and redemption– it is one more thread in the tapestry that says history is under divine control and moving toward a redemptive conclusion. In mystical circles, this belief also tied into ethical behavior – some taught that particularly righteous living could hasten the coming of the Messiah (a concept called zekhut, or merit). Combined with the Guf, one imagines that ensuring each soul fulfills its purpose on earth (through living righteously) could be part of repairing the world and completing the number of souls required.

The Seven Signs motif represents the checklist of destiny – a narrative convenience that helps believers feel knowledgeable about God’s plan. It often simplifies the complex imagery of prophecy into a linear sequence (“first this, then that…”), which makes the unfathomable idea of the end of the world a bit more concrete. Its mobilizing power lies in interpretation- if a preacher today can point to six out of seven signs as already fulfilled, the community may feel an intense urgency regarding the final sign. This kind of rhetoric has been especially visible in evangelical media. For example, during the Gulf War of 1990–91, some pastors proclaimed that the prophecies of Ezekiel (war in the Middle East) were being fulfilled – essentially saying “one of the last signs is happening before our eyes.” In recent times, the convergence of unusual natural disasters and global crises (tsunamis, pandemics, climate upheaval, international conflicts) has again been framed by some as signs of the end, often using the familiar trope of a finite list (“X number of signs and we’re almost there”). The cumulative effect is to maintain a community’s apocalyptic vigilance. It creates a shared lens for interpreting reality- believers become adept at seeing ordinary or tragic events as part of a divine program, which reinforces group identity and the authority of those who can “decode” the signs.

From a scholarly perspective, these apocalyptic beliefs and their associated predictions can be seen as part of eschatological myth-making – crafting a grand narrative of last things – and as tools for belief mobilization. They answer existential questions (why is the world like this? where is history heading?) with dramatic stories and promises. They can legitimate leadership (prophets and pastors who claim special insight into God’s timetable often gain devoted followings) and catalyze movements (as with Millerism birthing Adventism, or failed prophecy spawning new interpretations). The repeated failure of specific doomsday dates has not discredited the underlying myths for true adherents; instead, each failure often enriches the mythology. For instance, after 1844’s Great Disappointment, the Adventist mythos expanded to include the idea of a heavenly sanctuary cleansing (a doctrinal innovation that explained the non-event on earth). After 1914, the Jehovah’s Witnesses’ eschatological narrative adapted by teaching Christ had begun an invisible reign from that year, and the final end was still imminent – thereby retaining urgency but deferring the climax.

The Rapture, the Guf, and the Seven Signs each illustrate different facets of how apocalyptic expectations are woven into religious thought and history. The Rapture encapsulates the immediate escape and judgment motif in Christian eschatology, generating cycles of fervent expectation and occasionally disappointment. The Guf embodies a mystical completion motif in Jewish eschatology, quietly affirming that a divinely set fullness of time (or souls) must be reached before the new era begins. The Seven Signs (and analogous lists of portents) represent the structured unfolding of destiny, a template that both medieval monks and modern ministers have used to explain where we stand on the road to the end. Together, these concepts show how believers across ages and cultures have sought both knowledge and reassurance about the end of the world- knowledge, in the sense of clues or countdowns that make the mysterious end feel a bit more predictable; and reassurance, in the sense that history is not random chaos but a story with a divine conclusion. Even as specific predictions fail time and again, the underlying apocalyptic narrative endures, continually adapted with new dates, new interpretations, or new emphases – a testament to the powerful hold that the dream of an ultimate resolution, a final reckoning (be it through a rapture, a messianic arrival, or cosmic signs), has on the human religious imagination.

The 0% Success Rate- Analysis of Failures

It is statistically remarkable (and a touch darkly comical) that apocalyptic prophets have been wrong 201 out of 201 times. The score- World – 201, Doomsayers – 0. In sports terms, the prophets’ batting average is .000 – complete failure. The Doomsday Scoreboard’s tally shows “201 Failed Apocalypse Predictions So Far – 0 Successful”. The perfect failure rate is visualized in Figure 1 above, where the bar for failed predictions towers at 201, and the success bar is literally zero. In a field that claims divine revelation or secret knowledge of destiny, a zero-percent accuracy record is damning. By comparison, random guessing or flipping a coin would theoretically yield a better success rate if the end of the world were even remotely imminent over such a long period – but no one has ever guessed correctly, not even by accident.

Several factors explain this consistent failure. First, false assumptions underpin many prophecies- date-setters assume that ancient scriptures, personal visions, or astronomical coincidences provide a reliable timetable for cosmic events. History proves otherwise. No empirical or scriptural method has yielded a correct date. Often these predictions are unfalsifiable at the time – until the date passes and reality falsifies them. Importantly, many prophets use similar sources and techniques, which may contribute to their uniform failure. For example, biblical numerology (adding up ages, such as “7×70 weeks” and “666,” etc.) has been repeatedly employed to pinpoint a year or day for the Second Coming. Each time, the numbers have been either miscalculated or simply irrelevant to external events. The inherent vagueness of religious texts means they can be reinterpreted endlessly; any specific date drawn from them is more arbitrary than prophetic.

Moreover, cognitive biases practically guarantee failure. One is the “End-of-World Syndrome”-those predicting an imminent apocalypse usually believe they are living in uniquely significant times, a bias that psychologists note in each generation. Indeed, researchers find that end-time prophets often place the doomsday within their lifetime or within the next century, perhaps due to a mix of ego and genuine belief that “the signs all point to now.” However, every generation has had its crises and wonders; none has yet been the final one. Hindsight highlights how ordinary historical circumstances are often misinterpreted as extraordinary omens. For example, a comet, an eclipse, or a war might seem portentous through a prophetic lens, but from a longer scientific view, these events are regular occurrences or human-caused conflicts, not world-ending cataclysms.

Another crucial aspect is how failed predictions are rationalized. The social psychologist Leon Festinger’s classic study, “When Prophecy Fails,” examined a 1954 UFO doomsday cult. After their predicted apocalypse did not happen, many believers did not abandon the prophecy. Instead, they concocted explanations (e.g., their faith “saved the world” at the last minute) and even increased their zeal. The cognitive dissonance coping mechanism has been observed repeatedly. Jehovah’s Witnesses, after 1914 passed, argued that Christ had begun ruling “invisibly” in heaven – changing the prophecy rather than admitting error. Harold Camping, after May 21, 2011, passed away, claiming a “spiritual judgment” had occurred that day, deferring the physical end to October. Such rationalizations enable failed prophets (and their followers) to save face and maintain their faith, but they also further erode any claim to objective reliability. Each revision is effectively an admission that the method of prediction was flawed.

The unbroken string of failure is a robust empirical refutation of doomsday prophecy as a “knowledge” domain. If any one tradition or method had genuine insight, at least one apocalypse should have occurred as foretold. Instead, the failures are universal, cutting across all religions and cultures, indicating that apocalyptic predictions are not based on any valid source of information about the future, but rather on human factors that we must analyze – namely, the motives and patterns behind these prophecies.

Patterns by Tradition and Origin of Predictions

A striking pattern emerges from the record- most doomsday predictions have roots in Abrahamic religions, especially Christianity. According to scholarly surveys, “most predictions are related to Abrahamic religions, often echoing the eschatological events described in their scriptures”. Christian end-times scenarios (the Second Coming of Christ, the Rapture, the Last Judgment) dominate the scoreboard. The Doomsday Scoreboard notes that the “most anticipated apocalypse” in the dataset is the Second Coming of Jesus, reflecting how frequently Christian prophecy has set dates for Christ’s return. From early church figures like Hippolytus and Irenaeus (who expected Jesus by the year 500) to modern televangelists, the Second Coming/Messianic kingdom is a recurring theme. Similarly, the concept of the Rapture (the elect being taken up before tribulation) has inspired numerous American predictions (e.g., the 1840s Millerites, the 1910s-1920s Adventists, the 1970s evangelicals, the 1990s prophecy authors, and the 21st-century internet preachers) – all of which have proven to be incorrect.

Judaism and Islam have contributed far fewer date-specific apocalypse prophecies. Jewish tradition generally views the “end of days” as contingent and undated, although figures like Sabbatai Zevi in the 17th century and some medieval rabbis did attempt to assign dates (all of which ultimately failed). A notable Jewish calculation predicts the Messiah by the year 6000 of the Hebrew calendar (~2239 CE), followed by a subsequent 1000-year period of desolation. This is a theological expectation rather than a hard prediction, and time will tell its fate (with scientific skepticism warranted). In Islam, classic theology again avoids exact dates, but individuals have made attempts- e.g., Rashad Khalifa calculated an end in 2280 from Quranic numerology, and a 20th-century Sufi sheikh predicted Judgment Day before 2000 – which was clearly incorrect as 2000 has passed. Overall, Christian prophecy has been the most date-fixated, which tracks with Christianity’s strong apocalyptic canon (especially the Book of Revelation).

In contrast, Eastern religions, such as Hinduism and Buddhism, posit cyclic ages spanning thousands or millions of years (e.g., Kali Yuga) and have not historically produced the same kind of imminent doomsday dates – certainly not on the global stage. The cultural clustering of belief suggests that apocalyptic prophecies are culturally conditioned. People tend to predict the end in terms of their religious framework – e.g., Hindus in India did not warn of the biblical Armageddon, nor did medieval Christians worry about Kali Yuga; each culture’s “end” stays within its mythos. Regional exclusivity highlights that these scenarios are products of belief, rather than universally observed phenomena. If an actual apocalypse were evident or scheduled in nature, we would expect convergence in predictions; instead, we see divergence by culture, indicating human tradition at work, not divine revelation.

Within the Christian sphere, further patterns appear. Certain groups or individuals became repeat offenders in prophecy. The scoreboard highlights that the person with “most wrong predictions” is Harold Camping with 6 failed dates, and the group with the most is the Millerites with 3. Indeed, Camping doggedly predicted 1994 (three dates that year) and then 2011 (two dates), totaling five distinct failures (he is sometimes credited with a sixth recalculation). The Millerite Adventists collectively revised their expectation multiple times around 1843–1844. Likewise, Herbert W. Armstrong (Worldwide Church of God) promoted at least four dates from the 1930s to 1970s. Jehovah’s Witnesses’ leadership selected 1914, 1918, 1925, and 1975 (and some earlier dates, as per their founder, Russell) – effectively a string of at least five failed predictions across different decades. The repetition is not coincidental; it reflects an institutional or personal investment in the apocalyptic narrative. Once a group is oriented around an end-times belief, there is a tendency to keep adjusting the timeline rather than abandoning the belief. It becomes a core part of their identity and doctrinal system (as seen with JWs, who shifted from specific dates to a vaguer “this generation” concept after 1975). Similarly, conspiracy-minded prophets in secular or New Age circles (e.g., proponents of the Planet X/ X/Nibiru theory) have shifted their predictions from one date to another – 2003, 2012, 2017 – as each passing year moves the goalposts. Serial date-setting is a hallmark of the doomsday subculture.

Another pattern is the type of event predicted. We can categorize failed apocalypses into a few thematic archetypes-

- Religious Judgement/Second Coming- By far the most common. These involve Jesus Christ’s return, the rapture of believers, final judgment, or the arrival of the Messiah. Examples- virtually all Christian predictions (from 500 CE to 2025’s RaptureTok) fall here. Additionally, Islamic Mahdi/Messiah expectations (e.g., 1979 in some Shiite circles, not listed in the scoreboard, or the 2280 Quran code) fall into this category. These predictions rely on scriptural prophecies interpreted in a literal and immediate way, often combined with calculations (e.g., the “6,000 years since creation” idea popular in the 19th century and JW predictions). Outcome- all dates misinterpreted or simply wrong in timing.

- Cosmic Catastrophes – These involve natural events that destroy Earth, such as comet impacts, rogue planets, planetary alignments that cause floods or earthquakes, supernovae, etc. Examples- 1524 planetary alignment flood, 1910 Halley’s Comet gas, The Jupiter Effect 1982 (aligned planets causing quakes), 2011 Comet Elenin panic, 2012 Nibiru/planet X collision scenarios. Scientific analysis has debunked each- e.g., planetary alignments have a negligible gravitational effect (the Jupiter Effect was refuted by physicists well before 1982), and NASA confirmed that no rogue planet or asteroid was due in 2012. In fact, NASA scientist David Morrison explicitly called the 2012 Nibiru stories a “hoax” fueled by internet fake science. To date, all predicted cosmic doom events have either not occurred or caused no harm. (Notably, real extinction-level asteroids do exist, but prophets have predicted none – they are found by astronomers and expected in timelines of millennia, not specific years soon.)

- Human-Caused Destruction (war/technology)- Predictions that human action (usually war or nuclear) will end the world by a prophesied date. Examples- 1914–1918 by some early Watchtower publications (foreseeing an anarchic collapse of Christendom by 1920); 1950s fears of nuclear holocaust (Jim Jones predicted nuclear war in 1967; others in the 1980s predicted a Soviet-American war as Armageddon – e.g., Louis Farrakhan during the 1991 Gulf War claimed it was the “final war” of Armageddon). 1999 had many secular war/terror fears (Nostradamus’s vague 1999 prophecy was often interpreted as nuclear war or doomsday war). Y2K (2000) straddled technology and man-made collapse- some, like Jerry Falwell, suggested Y2K computer failures would be God’s judgment or allow the Antichrist’s rise. Outcome: No predicted wars or collapses occurred on schedule. While humanity could certainly self-destruct through war or ecological disaster, none of those specific forecasts proved accurate – they were more extrapolations of contemporary anxieties than genuine predictions. For example, the Gulf War of 1991 ended in weeks, not Armageddon; the Cold War ended with a whimper, not a bang, in 1989–1991, defying many evangelical prophecies of a fiery end from the 1980s.

- Mystical/Occult and New Age Prophecies- These often revolve around esoteric knowledge, psychic visions, or syncretic beliefs. Examples- Nostradamus (interpreters wrongly pegged July 1999 for doomsday from his quatrain), Jeane Dixon (psychic who predicted a 1962 planetary alignment would end the world – it did not – and later said Armageddon in 2020, also wrong), José Argüelles (New Age guru behind the 1987 “Harmonic Convergence,” implying global transformation or doom unless enough meditated – no evident effect), Heaven’s Gate cult (blended UFO lore with biblical ideas; they committed suicide in 1997 believing a spacecraft behind Comet Hale-Bopp would take them – a tragic false belief). These predictions frequently use symbolism and non-scientific sources (tarot, trance, “channeled” alien messages, etc.). Their failure highlights that subjective visions are not reliable forecasts. For instance, one cult leader predicted God in a UFO on March 31, 1998, in Garland, Texas – media and police watched; nothing happened. The semiotics here often involve modern myth (aliens, cosmic consciousness) rather than scripture, but they share the same outcome- nothing occurs outside the believers’ imaginations.

Despite differences in theme, a typical rhetorical pattern ties these prophecies together- urgent, absolute language and appeal to a higher authority. Predictors rarely say “maybe” – they insist the end “will” occur on X date, often citing a divine source (“the Bible clearly says…,” “God revealed to me…”) or a purportedly infallible calculation. They employ rhetorical devices of fear and salvation, using fear by describing horrific cataclysms (fire, flood, demons, war) that await the unprepared, and hope by offering a path to salvation or safety (join the group, repent, buy supplies). Apocalyptic rhetoric often paints a stark ‘us vs. them’ scenario – the faithful versus the doomed – which can galvanize in-group identity. For example, many Christian pamphlets warned readers to be among those “raptured” and not left behind to suffer. Cult leaders have used doomsday deadlines to enforce loyalty (“there is no future outside the group if the world ends next month”). Linguistically, these messages often employ biblical archaic phrasing (“the end is nigh”, “tribulation”, “the Beast”, “signs in the heavens”) or scientific-technical jargon misused (as in pseudo-scientific claims- “magnetic pole shift”, “planetary alignment gravitational resonance”) to sound authoritative.

Forensic linguistic analysis of various prophecies can even identify the subculture of origin. For instance, if a prediction text references “144,000 elect” and “the Antichrist’s reign”, it likely stems from a Christian millenarian context (the number 144,000 is a Revelation reference popular with Millerites, Jehovah’s Witnesses, etc.). If it speaks of “Age of Aquarius” or “vibrational harmony,” it is clearly New Age. Mentions of “Mahdi” or Quran verses mark an Islamic context. Terms like “Shambhalla” or “galactic federation” point to UFO/New Age cults. Thus, these prophecies carry semiotic signatures – symbols and code-words – revealing their doctrinal DNA. Despite surface differences, however, they all share a failure to convert words into reality.

Cognitive, Psychological, and Sociopolitical Drivers

Why do people keep making – and believing – apocalypse predictions against all evidence? The persistence of this phenomenon suggests that it addresses deep-seated psychological and social needs.

Cognitively, humans are pattern seekers and meaning makers. Apocalyptic prophecies often stem from the cognitive bias of apophenia, which involves perceiving meaningful connections in random or unrelated events. For a prophecy believer, disparate events (a pandemic, a blood moon, a war) snap together as fulfilling a grand pattern or prophecy. They can be fueled by confirmation bias – they notice news that fits (e.g., earthquakes, instability) and interpret it as “signs of the end,” while discounting contrary evidence (e.g., years of peace or normalcy). Additionally, the availability heuristic plays a role- vivid descriptions of destruction (from scriptures or movies) stick in the mind and make the idea of apocalypse feel more plausible or imminent than statistics would suggest.

Psychologically, apocalyptic belief provides a specific emotional payoff. Paradoxically, for some individuals, imagining the end of the world can be comforting or exciting. University of Minnesota neuroscientist Shmuel Lissek explains that having a predictable end date for the world turns the ultimate unknown (death) into something scheduled, which can reduce anxiety about uncertainty. Knowing when the end will come – even if it is terrible – means one no longer worries if it will come randomly. Strangely, “apocalyptic beliefs make existential threats… predictable,” helping believers relax about an uncertain future. This is supported by experiments- when a shock or unpleasant event is guaranteed to occur at a known time, subjects feel less anxious than if it could happen at any time.

For some, especially those who feel marginalized or traumatized, there is validation in fatalism. If one’s personal life or society at large seems irredeemably troubled, the idea that “it is all going to end soon” can be a form of catharsis or a sense of justice. Psychologists note that individuals with past trauma or powerlessness may gravitate to doomsday groups where their worldview – that the world is imperfect and must be swept away – is socially reinforced. In these groups, attributing the world’s evil to a cosmic plan (e.g., “God will punish the wicked, we the elect will be saved”) removes personal responsibility and provides a sense of moral order. It can also satisfy an emotional craving for secret knowledge and significance- Believers often feel they are “in on a grand secret” that the rest of the world ignores. They feed the ego and a sense of meaning – they might be ordinary people, but if they think they know how and when the world ends, they feel special, chosen, or simply smarter than the “sheeple.” Conspiracy psychology research shows overlap here- a “feeling of powerlessness” and mistrust of authority correlate with both conspiracy belief and apocalypse belief. Embracing an end-of-world narrative often includes believing mainstream authorities (scientists, governments) are lying or ignorant, while the believer has real insight. They restore a sense of power or control in one’s worldview.

There are also sociopolitical uses of apocalyptic prophecy. Leaders and movements throughout history have weaponized doomsday predictions to serve earthly agendas. Politically, an imminent apocalypse can justify extreme actions and suspensions of everyday ethics – “the end is near, so drastic measures are needed.” For example, revolutionary movements or cults might urge followers to donate assets, isolate themselves, or even commit violence (as seen in some militant cults), arguing there is no future to worry about. During the Cold War, some religious groups fused anti-communist politics with prophecy, framing the USSR as Gog/Magog and nuclear war as God’s plan – thereby supporting militaristic attitudes as pragmatic but divine. Sociologically, apocalyptic predictions often surge in times of social stress or rapid change. The year 1000, the Black Death era, World War I and World War II, the turn of the millennium, and the 2020 pandemic – all these upheavals saw spikes in end-times talk. People turn to apocalyptic narratives to make sense of chaos. It provides a simple storyline (“these troubles mean the End is coming”) in a complex, scary world. As one psychiatrist observed, in complicated, fearful times, people may romanticize or yearn for a simpler post-apocalyptic world- some “imagine surviving and thriving” after society’s collapse, seeing it as a reset or escape from modern pressures. A notable trend was the youth fascination with zombie apocalypses – a fantasy of living in a world with no school, no bills, just survival adventures. While that is more pop culture than religion, it taps into a similar psychology- apocalypse as an adventure or solution to present problems.

Crucially, these psychological and social drivers operate largely outside of conscious awareness for believers. They genuinely think they have rational or revelatory reasons for the date (the math “works out,” the vision felt real, etc.), not realizing how much their desire for certainty, meaning, or justice is fueling those calculations. A believer often experiences a powerful emotional reinforcement when joining an apocalyptic movement – a mix of fear (which heightens arousal and group cohesion) and hope (soon we will be vindicated). Emotional cocktails can be addictive. It also explains why, even after repeated failures, the apocalyptic narrative persists. The core promise is too psychologically satisfying to give up the idea that today’s injustices will be abruptly overturned, that believers will be saved and enemies punished, and that one’s life is on the cusp of cosmic significance. That hope can survive many disappointments. Sociologist John Hall noted that after prophecies fail, groups often do not disband but instead reinterpret and continue, because the social bonds and identity built around the prophecy are stronger than the disconfirmation. In other words, believers may say, “Date X was wrong, but the end will still come – and we are still the ones who know.”

Finally, cultural reinforcement cannot be ignored; in some communities, apocalyptic beliefs are normalized. For instance, in American evangelical subculture, expecting Jesus’ return “any day now” is common – so specific date-setters find a ready audience primed to accept that premise, even if they reject past false alarms. In places where millenarian religion is strong or education in science is weak, prophecy finds fertile ground. By contrast, secular and scientific communities treat such predictions with skepticism or humor, meaning fewer people in those circles get drawn in. This is why, for example, a doomsday claim might cause panic in one segment of the population but be virtually unknown in another. The sociopolitical context, including media portrayal, determines how far and how fast these ideas spread. The 2012 prophecy gained global attention due to internet and TV coverage; older prophecies were often spread via revival meetings or pamphlets. Today, social media can rapidly amplify a fringe prediction (like the TikTok Rapture of 2025) to millions. The psychology of viral content means dramatic, scary claims travel quickly, often without critical checks. The new media landscape has, in some ways, made us even more vulnerable to spreading apocalyptic memes – a challenge which shows the need for robust scientific literacy and critical thinking.

Scientific Reality Check- Why Apocalyptic Claims Fail

From a scientific and empirical standpoint, none of the major apocalyptic claims withstands scrutiny. Cross-examining each type of prediction against current knowledge reveals fundamental flaws or impossibilities in the prophecy narratives.

Astronomical and Geophysical Claims – Many doomsday prophecies invoke cosmic disasters, such as asteroid impacts, rogue planets, solar flares, and planetary alignments that can trigger earthquakes, among other phenomena. Modern science has extensively studied these phenomena-

- Asteroids/Comets- Large impacts are indeed extinction-level events, but they are extremely rare. NASA’s Planetary Defense Coordination tracks near-Earth objects and can predict close approaches decades in advance. As of 2025, no known asteroid is on course to hit Earth in 2026 or any imminent year at a civilization-ending scale. No astronomical observation supports the 2026 asteroid collision predicted by a fringe sect – it is pure fiction. Past comet panics (Halley in 1910, Kohoutek in 1974, Hale-Bopp in 1997) were similarly unfounded. For Halley’s Comet, scientists understood that the comet’s tail gases are far too diffuse to poison Earth’s atmosphere. Indeed, in 1910, Earth passed through the tail with no effect, disproving Flammarion’s doomsday claim. When Comet Elenin approached in 2011, there were widespread fears that it would trigger earthquakes or collide; astronomers pointed out that the comet was small and would miss Earth by a considerable distance, which it did, with no impact. NASA and astrophysicists consistently stress that extraordinary cosmic events are either predictable and far in the future or extraordinarily unlikely at any given moment. For instance, a nearby supernova or gamma-ray burst could be catastrophic, but probability estimates suggest such events are millions of years away. The specific dates chosen by prophets have no scientific basis; they are essentially random or numerological, unconnected to actual celestial mechanics.

- Planetary Alignments- The idea that planets lining up cause disasters was popularized by pseudoscience (e.g., the 1982 “Jupiter Effect”). The gravitational pull of planets in alignment is negligible compared to the daily forces the Earth experiences (the moon and sun’s gravity dominate tides and tectonics). No earthquake or tidal wave has ever been linked to planetary alignment. As one scientific source noted, none of the proposed alignment catastrophes are possible – they violate fundamental physics. Indeed, multiple planetary alignments have occurred throughout history without incident. So, any prophecy hinged on an alignment (1524, 1982, 2000, etc.) was doomed to fail.

- “Planet X” or Nibiru Collisions – The modern myth claimed a hidden planet would smash into Earth by a certain year (2003, then 2012, and later dates). NASA categorically debunked Nibiru as a hoax – if a planet were on a collision course with Earth in those years, it would have been the brightest object in the sky long before impact, making it impossible to hide. No such object was ever detected because it does not exist. As physicist David Morrison put it, “the widespread internet rumor that the world will end in [2012] due to some astronomical event is a complete hoax”. He emphasized that these claims were driven by fake science websites and marketing for fiction, not fundamental astronomy. The same applies to any future Nibiru-style prediction – unless the laws of orbital mechanics cease, a surprise planet cannot appear out of nowhere on a specific date.

- Supernovae/Gamma-ray bursts – Some scientific discussions note potential risks (e.g., the star WR 104 might go supernova in ~300,000 years, potentially pointing a GRB at Earth, but this is unlikely). Importantly, scientists frame these in terms of probability and vast timescales. Any prophet claiming a star will explode and fry Earth next year is ignoring actual stellar lifecycles and observational data. No star in our vicinity is poised to blow imminently at extinction level; the closest candidate (Betelgeuse) might go supernova in the next 100,000 years – or it could be tomorrow, but crucially, even that would likely not harm Earth (just an incredible light show).

In short, the cosmos offers no support for date-specific apocalypses. When prophets co-opt scientific language (such as the use of terms like “asteroids” and “shifting poles”), they invariably distort or ignore actual scientific findings. Scientists are typically happy to explain why such scenarios are unfounded, and history vindicates the scientific perspective every time – no surprise asteroid, no mystical alignment catastrophe, no hidden planet.

Biological and Ecological Claims- Some modern apocalyptic ideas revolve around plagues, climate change, or ecological collapse. Interestingly, classic religious prophecies did not specify these, though Revelation mentions plagues as part of the tribulation. In 2020, a few voices framed COVID-19 as an end-times plague. While pandemics are tangible and devastating, the claim that one pandemic would literally “end the world” by a divine plan on a set date is not scientific. Epidemiology can predict spread and fatality rates, but not align them with prophecy. COVID-19, for instance, though tragic, has not brought civilization to a collapse; human science and cooperation are overcoming it. Climate change is a severe global crisis, but its worst effects unfold over decades, not a sudden doomsday. If someone says, “the world will end by 2060 from climate disaster as prophesied,” science would counter that while climate change can cause immense suffering, it is a progressive challenge with many possible futures, none of which equate to a literal apocalypse on schedule. The complexities of Earth systems defy the simplistic, punctual disaster scenarios of prophets prefer.

Theological Prophecies vs. Evidence- By definition, supernatural claims (like the Rapture or Second Coming) lie outside direct scientific falsification – one cannot disprove that “Jesus will return” in the same way one disproves an asteroid collision, because it is a matter of faith. However, we can analyze the evidence around such claims. After dozens of predicted Second Comings have failed, the burden of proof is squarely on those making new claims. Furthermore, even theology provides counter-arguments- the Bible itself warns that “of that day or hour no one knows” (Mark 13-32) – which should caution Christian predictors that setting dates is presumptuous. Indeed, every prominent church or sect that set a date has faced embarrassment, leading many Christian denominations today to distance themselves from date-setting. The Catholic Church, for example, does not endorse any specific timeline for the end, treating extreme millennialism as fringe. From a rational perspective, any prophecy that claims direct divine scheduling of the end lacks empirical support and often contradicts the source scripture’s admonitions. Moreover, unlike in antiquity, today if someone claims, “I heard God say the world ends next week,” we have abundant precedent to doubt their personal revelation – consider the hundreds of prophets before who claimed divine authority and were wrong.

Statistical Falsifiability- There is a tongue-in-cheek but logically sound point- If someone truly had a gift or method to predict world-ending events, why have they been consistently wrong 200+ times? We routinely test alleged psychics and prognosticators (e.g., about ordinary events or gambling outcomes) and find no evidence of actual predictive power. Apocalyptic prophets are like psychics who only predict “someday, a huge event will happen” and keep getting the details wrong. Statistically, if the world were ending on a random date in the last 2000 years, the chance that none of the 200+ predictions hit the mark is astronomically low – unless those predictions were never based on actual signal, only noise. It is akin to 200 archers, all missing a target that is not there. The record falsifies the proposition that “some people know when the end will come.” They clearly do not.

Scientists approach future risks differently —via models, probabilities, and observation, rather than scripture or private visions. For example, astrophysicist Nick Bostrom estimated the frequency of 1-km asteroids hitting Earth (~1 per 500,000 years). That implies ~0.0002% chance in any given year – not zero, but extremely small. A prophet who says “an asteroid will hit next year” is effectively claiming a near-impossible coincidence with no data backing. Similarly, geologists say a supervolcano could erupt within the next 100,000 years (like the Toba eruption 75,000 years ago). However, if someone claims that Yellowstone will erupt exactly in 2025 based on a vision, scientists will note that there are no geological signs of an imminent eruption on that schedule. Moreover, in 2025, Yellowstone remains quiet. Time and again, scientific monitoring trumps prophetic alarmism- e.g., when prophets proclaimed doom by nuclear war on specific dates, political scientists and historians could point out that while nuclear war is a risk, it tends to be deterred by rational actor strategies – and indeed, cooler heads prevailed at those supposed end dates.

Even in scenarios where a global catastrophe is possible (nuclear war, pandemic, etc.), specificity is the giveaway of a false prophecy. Science can warn “if X continues, disaster could result in decades” (like climate change) – but whenever someone says, “On July 29, 2026, at midnight, the world will end,” you can be virtually sure they are wrong. Complex systems (geopolitical, ecological) do not operate on neat timetables revealed to solitary gurus.